If all four, quadruply redundant flight computer modules fail, there is a fifth, entirely separate computer onboard, running different code to get the spacecraft home. Finally, it comes home, reentering the Earth’s atmosphere at 11 km per second, slowing itself with a heatshield and parachutes, and splashing down in the Pacific not far from San Diego. It swoops within 110 kilometers of the lunar surface for a gravity assist, then heads 64,000 km out-taking more than a month but using less fuel than it would in closer orbits.

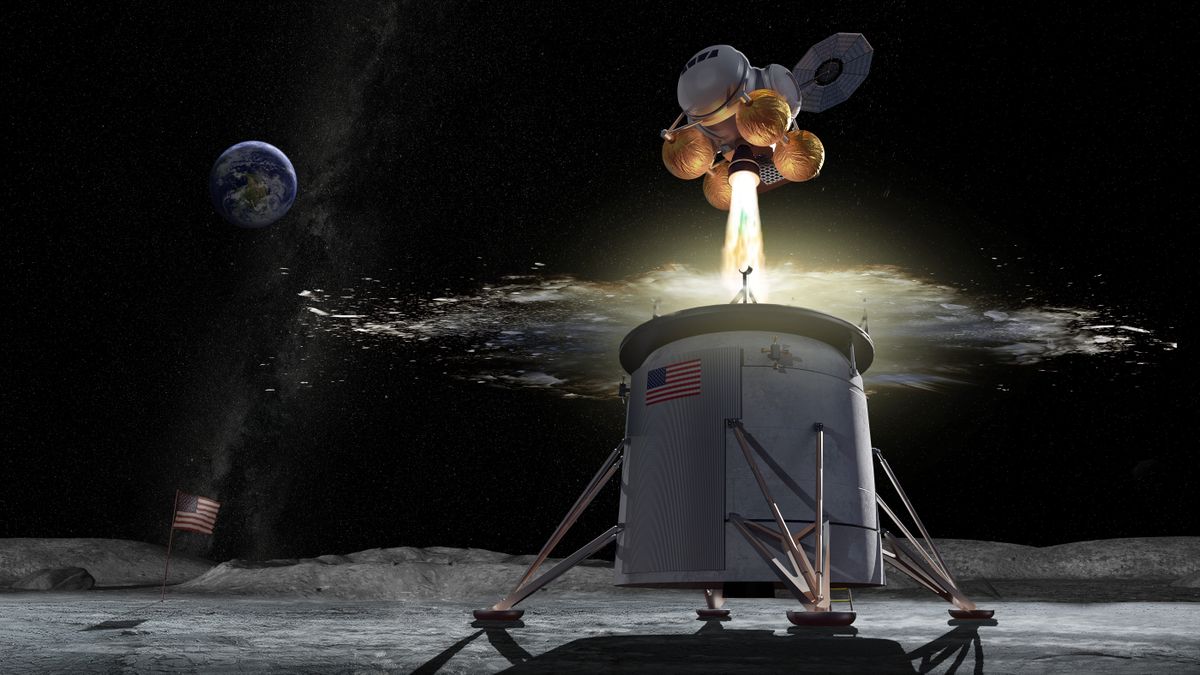

( Apollo 11 lasted eight days.) The ship roughly follows Apollo’s path to the moon’s vicinity, but then puts itself in what NASA calls a distant retrograde orbit. The Artemis I flight is slated for about six weeks. “I have a name for missions that use too much new technology,” he recalls Casani saying. Roger Launius, who served as NASA’s chief historian from 1990 to 2002 and as a curator at the Smithsonian Institution from then until 2017, tells of a conversation he had with John Casani, a veteran NASA engineer who managed the Voyager, Galileo, and Cassini probes to the outer planets. And capsule shapes happen to be really good for coming back into the atmosphere at Mach 32.” “The laws of physics haven’t changed since the 1960s. “There are certain fundamental aspects of deep-space exploration that are really independent of money,” says Jim Geffre, Orion vehicle-integration manager at the Johnson Space Center in Houston. NASA says there is no need to reinvent things engineers got right the first time. Just look at Orion’s crew capsule-a truncated cone, somewhat larger than the Apollo Command Module but conceptually very similar. Perhaps more important, the project inherits basic engineering from half a century of spaceflight. “I have a name for missions that use too much new technology-failures.” -John Casani, NASA And the large maneuvering engine in Orion’s service module is actually 40 years old-used on 19 space shuttle flights between 19. The rocket’s apricot color comes from spray-on insulation much like the foam on the shuttle’s external tank. Much of Artemis’s hardware is refurbished: Its four main engines, and parts of its two strap-on boosters, all flew before on shuttle missions. On Artemis I, the first test flight, mission managers say they are taking the SLS, with its uncrewed Orion spacecraft up top, and “stressing it beyond what it is designed for”-the better to ensure safe flights when astronauts make their first landings, currently targeted to begin with Artemis III in 2025.īut Nelson is right: The rocket is retro in many ways, borrowing heavily from the space shuttles America flew for 30 years, and from the Apollo-Saturn V. But it’s a totally different, new, highly sophisticated-more sophisticated-rocket, and spacecraft.”Īrtemis, powered by the Space Launch System rocket, is America’s first attempt to send astronauts to the moon since Apollo 17 in 1972, and technology has taken giant leaps since then. “Looks like we’re looking back toward the Saturn V. “When you look at the rocket, it looks almost retro,” said Bill Nelson, the administrator of NASA. Mission managers say Artemis will fly when everything's ready-but haven't yet specified whether that might be in late September or in mid-October.

#PROJECT ARTEMIS NASA UPDATE#

Update 5 Sept.: For now, NASA’s giant Artemis I remains on the ground after two launch attempts scrubbed by a hydrogen leak and a balky engine sensor.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)